Matthew Capuano-Rizzo

Matthew Capuano-Rizzo

Photo: Youth attendees at CCL’s Third Coast February Conference –Princella Talley/CCL

Citizens’ Climate Lobby’s summer conference focused a large amount on diversity and environmental justice, gathering climate leaders from around the country

Citizen’s Climate Lobby (CCL) is an environmental group with more than 400 local chapters in the United States. Their advocacy work focuses largely on carbon-pricing and their signature bill The Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act has 80 cosponsors in the House of Representatives. If implemented, the bill would reduce US carbon emissions by 40% in the next 12 years.

On June 13, CCL hosted a virtual climate conference called “A Community Stronger than COVID.” The conference was attended by 3,544 unique viewers on Zoom, viewed by 764 people on Twitter, 222 people on Facebook Live, and 154 people on Youtube. All together 4,685 people participated in CCL’s June Conference. The conference had a plenary session with 3 members of Congress and 7 tracks on different themes that included the details and advocacy strategy of CCL’s bill, how to integrate faith and academic groups in climate advocacy, as well as several sessions on environmental justice issues and inclusivity. In addition to highlighting climate justice and the Innovation Act as an effective and equitable solution to the climate crisis, the group also announced their support for the RECLAIM (Revitalizing the Economy of Coal Communities by Leveraging Local Activities and Investing More) Act. The bill, according to its description, would provide funds to States and Native American nations for the purpose of “promoting economic revitalization, diversification, and development in economically distressed communities through the reclamation and restoration of land and water resources adversely affected by coal mining carried out before August 3, 1977. ” I attended several sessions on diversity in the climate movement and one session on revitalizing coal communities. By seeking to include economically disadvantaged and underrepresented communities, CCL is an example of an organization incorporating the social aspects of the climate crisis in its advocacy efforts.

Inclusive Climate Advocacy

The first session I attended was titled “Inclusive Climate Outreach in the American South” and was led by CCL’s Third Coast Regional Coordinator Susan Adams and CCL’s Development Associate and Diversity Outreach Coordinator Princella Talley. Adams explained that Latinos (69%) and African Americans (57%) are more concerned about global warming than their white peers (49%). Such groups lack of representation in large environmental organizations such as CCL, thus does not stem from a lack of interest in the climate crisis, but rather a lack of inclusion. To address this disparity, Adams and Talley set out to engage minority communities in the Third Coast Region (Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi). In their February 8th Conference in Houston entitled “United We Stand,” the pair invited local middle schools and even a baptist church whose pastor, Joseph Lewis, brought 47 youth and congregation members to the conference.

Adams illustrated how white CCLers can engage underrepresented groups in their chapters in three steps “1. Listen 2. Listen 3. Listen.” She emphasized that listening and acting on Pricella’s understanding of the historical context of the South (in lynchings, disenfranchisement, and enduring voter suppression) was the key to the team’s success. Talley underscored that the United States, particularly in the South, has a strong opposition to African Americans expressing political will. Blatant examples include current Georgia governor Brian Kemp’s purging of 1.4 million voters, closing of more than 200 polling places and holding up of tens of thousands of voter applications, nearly all of them from African American applicants, between 2012 and 2018. He, undoubtedly won that election over Stacey Abrams. Voter ID laws, registration requirements, voter purges, felony disenfranchisement, and gerrymandering deny millions of Americans of the right to vote, particularly Black Americans, one in 13 of whom cannot vote due to disenfranchisement laws. Thus, Talley reasoned that diversity cannot be a ‘corporate goal’ or a ‘nice to have,’ but a lifestyle commitment and a ‘must-have.’ “If your goal is to expand diversity, you have to accept solutions that conflict with your lived experiences,” she explained. To achieve equity, which according to Northeastern involves “giving everyone in a situation the specific tools that they need to be successful,” organizations ‘must have people of color as leaders and participants.’ According to Talley, an equitable approach to climate solutions necessitates ‘learning communities issues and concerns,’ ‘identifying barriers,’ ‘working with community leaders,’ ‘creating access,’ and ‘living your commitment.’ Such an approach relates to CCL’s focus on lifting up economically disadvantaged communities moving ‘Beyond Diversity’ to real inclusion.

Coal Country

The second session I attended was led by Brandon Dennison, founder and CEO of Coalfield Development, a support network for a family of social enterprises in West Virginia. Dennison explained that growing up in West Virginia, he felt that his state was failing to achieve its full potential by relying so heavily on one resource: coal. The state is one of the poorest in the country and it suffers from high levels of pollution and related diseases, poor drinking water, and addiction. Dennison sees coal as the root of many of these social and economic problems. People living near mountaintop removal sights, for example, “disproportionately experience cardiovascular disease, birth defects, and lung cancer.” To provide West Virginia’s residents with more opportunities and diversify the state’s economy, Dennison set about partnering with individuals to create, invest in, and maintain social enterprises. The group started solar company Solar Hollar, organic farming company Refresh Appalachia, a community-based real-estate arm and many other social enterprises. Targeting people on public assistance or in recovery, Coalfield Development provides ‘crew members’ with a 33-6-3 workforce development program. The program involves 33 hours per week on job training, 6 hours per week in community college studying Applied Sciences, and 3 hours per week on personal development coaching.

The organization so far has trained 1,200 people, created 250 jobs, started and supported 52 businesses, generated $20 million in new funding for the region and revitalized 200,000 square feet of formerly dilapidated property, according to the group’s founder Brandon Dennison. Coalfield Development is funded by grants from the Appalachian Regional Commission, private grants, and more than 40 different foundations in addition to revenu from its social enterprises. Instead of simply informing coal communities that their main source of revenu is obsolete, Coalfield Development provides them with many alternatives and job training. Partnering with communities is essential, particularly considering the fact that if adopted, the Carbon Dividend and Energy Innovation Act would essentially eliminate coal from the power sector by 2030. Even without the Innovation Act (which Dennison said should be adopted), coal will continue to decline sharply as “investors and insurers back away.” Providing communities with the tools to move away from a business that has poisoned their air and water and spread countless diseases all while providing steady income will be essential as we continue to decarbonize our economy. In the last segment, the conference focused on moving beyond diversity to real inclusion of people of color in the climate movement.

Belonging and Inclusion

In the final segment of the weekend, Karina Ramirez, CCL’s Climate Education and Diversity Outrach Manager and Clara Fang, CCL’s Climate Education and Student Engagement Coordinator, focused on the concept of environmental privilege and discrimination in the US Conservation movement. Environmental privilege according to Environmental Studies Professor David Pellow at the University of California, Santa Barbara is defined as “the ability of privileged groups to keep environmental amenities for themselves and deny them to less privileged groups.” While most of the people on the call, according to the Zoom survey data, grew up in a town with clean air, for example, according to the World Health Organization 9 out of 10 people worldwide breathe polluted air. Such pollution is responsible for around 7 million premature deaths per year from related diseases such as stroke, heart disease, and lung cancer. Pollution is also not colorblind. Research from the National Academy of Sciences found that “Non-Hispanic Whites experience about 17 percent less pollution than they cause, while Hispanics are exposed to about 63 percent more air pollution that they cause. And Black people are exposed to about 56 percent more air pollution than they cause.”

When we think of solutions to the climate and larger environmental crisis, we often think of big environmental groups. Fang emphasized that groups such as the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society who started the US Conservation movement were essentially wealthy clubs for white men who were ‘beneficiaires of capitalism, racism, and patriarchy,’ and largely ‘uninterested in addressing social inequalities.’ Such claims are supported by research. Leading conservationists such as Madison Grant, a political ally of Teddy Roosevelt, were also white supremacists. Grant wrote the 1916 book “The Passing of the Great Race” that warns readers of the decline of ‘Nordic’ peoples. Grant’s work influenced the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 that banned immigrants from the Middle East and Asia and greatly restricted immigration from Eastern Europe and Africa. Grant’s admirers ranged from Teddy Roosevelt to Adolf Hitler.

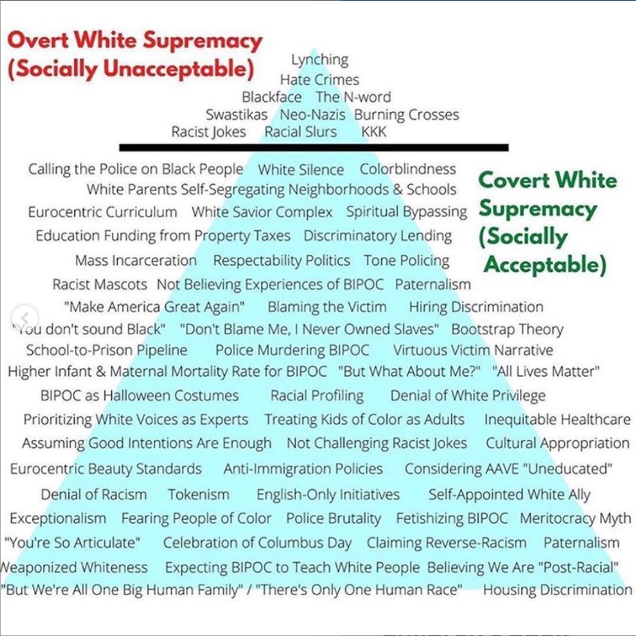

The pair also underscored that much of our protected land and national parks were stolen from Native Americans. Specifically, Yellowstone, Glacier, Badlands, Mesa Verde, the Grand Canyon, and Death Valley were all ethnically cleansed to make way for what Roosevelt, those who followed him, and many others saw as “America’s best idea.” Karina Ramirez, then connected Fang’s history lesson to present day. “After hundreds of years of colonialism and racism, it’s no wonder that people of color don’t feel safe in environmental organizations and are reluctant to call themselves environmentalists,” she affirmed. People of color make up 40% of the US population and by 2033, the majority of the US population will be people of color. In a sharp contrast, research by Green 2.0 found that 88% of staff and 95% of boards of environmental groups were white. After highlighting this disconnect, the pair illustrated how racism pervades every aspect of our society, including a graphic from @theconsciouskid Instagram page (pictured below). To improve CCL’s diversity, Ramirez pointed to the group’s increased commitment to taking racial statistics and outreach efforts to underrepresented communities. She created, for example, the Latinos Action team and developed a Spanish-language website for Citizens Climate Lobby. Now, CCL regularly hosts events in Spanish, including two of the June conference sessions.

-Credit: @theconsciouskid

Thus, as protests continue around the world to denounce institutional racism, we, in the environmental movement, must recognize that such calls include us too. That we also must change. We also must reach out: to communities instead of simply wondering why they are not coming to our events. We also must confront: social issues such as racism and inequality instead of pretending they don’t concern us. And most of all, we must listen: to voices that are often silenced.

If you are interested in CCL’s work, please join! You may also watch the conference recordings and follow CCL on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram!

Leave a Reply